Steven Mitchell, Mount Hood History

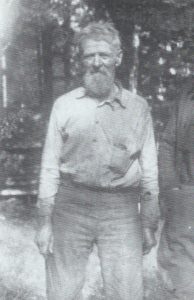

Steven Mitchell was legend on Mount Hood in his times, as well as his son Arlie, who was the last tollgate keeper at the Rhododendron Tollgate of the old Barlow Trail Road. Lige Coalman, who was raised by Steven, was also a legendary mountain man on Mount Hood in his own right.

Steven Mitchell – Portland Oregonian Sept 12 1920

“Steve Mitchell – Husband of the Hills

Man of the mountains

Whose Life Near Mount Hood Is a Story Book of Many Treasures

By Earl C. Brownlee

For 60 years Steve Mitchell, husband of the hills, has been fleeing, terrified, from civilization.

Yet the dreaded ogre as pacing at his heels again, debauching the icy waters of his streams of melted snow, defacing the majesty of his brilliant autumn hills, slaughtering the game that gave him his meat and heaping its insults upon injuries suffered at its hands.

The dusty road before his cabin door, an artery that helped to carve from the wilderness of woods, is leading multitudes of folk through the most wonderfully romantic section of the land of the last frontier.

And from end to end of the timber bordered highway of delightful vistas there is nothing or no one so romantic as Steve himself; Steve Mitchell, as old as the mountains he loves so well-the last of a sterling generation of brave men who revered the quiet grandeur of the hills above all other things.

Far from the paths of man’s progress Steve Mitchell many years ago sought the realm of heart’s desire. To achieve his goal this man of the mountains first cut his way as a workman over what became, by dint of labors like his, Portland’s Hawthorne avenue. With the street completed, civilization advanced and Steve Mitchell fled to far places again, cutting roadways as he went, into dark forests the circled Mount Hood.

There he found his glorious freedom and there he has remained, while time has etched its wrinkles on his face and has woven a mantle of white for his brow.

Meanwhile, he has reared and sacrificed to man’s estate four splendid sons and two accomplished daughters, among whom are those who have forsaken the ways of their grizzled father and have found success in the hated city.

“Confounded thunder buses” roll by his forest-bound home in ceaseless numbers nowadays as Steve Mitchell peers peacefully into the future for a spot where the profits and pleasures of men cannot be encroached.

In the ‘60s Steve Mitchell looked into the west from his home in Iowa. He kept faith with the vision and from a point near Cleveland, Ohio, he started the pilgrimage.

“And I’ve been tinkering aling ever since,” he says, as he declares he has other distances to gain.

Briefly, his tinkering was centered in mines of gold in California, but in 1866 he came to Oregon. He helped build streets through the timber and then built roads to and through Sandy to the mountains.

About the man and his life many tales are told, but none more truthfully nor well then Steve can tell them. There’s the story of his gold claim to entrance the mountain novice.

It is said that far back on the Salmon River, concealed for nearly half a century against the prying eyes of friends and enemy, Mitchell has a gold mine.. There, the story has it, he chips great nuggets from a rocky wall whenever he’s in need of funds and brings them to the counting house. The claim is a priceless treasure, we are told, that would yield the cost of every comfort if its owner chose.

“Bah!” Steve Mitchell will exclaim if you inquire into the story. “There are more lies in these hills than there wever were cougars.

“Liars, thunder buses and a new kind of man-animal with a whooping sort of holler are the torments of civilization. There’s too much civilization in the world.

“If you write articles tell about these man-animals who have come into the hills to pollute God’s creeks by washing their unworthy feet in them and tearing the quiet night with their whooping hollering. They’re ornery-worse than a cougar, and a couple of ‘em aint very far away.”

Folks don’t know the mountains, Steve Mitchell says, and can’t love their dim trails and rocky peaks as he does. Wedded to their wonders, Mitchell has learned their lore as the schoolboy learns from books; in them he has built his home and in them he will find his grave.

In the interim, though, there has been a lifetime of marvelous days, attended with thrills at times, yet always mandatory in their hold upon the heart of this fine fellow.

Steve was bent over a kitchen stove, when by inquisitiveness born of long acquaintance, he was interrupted, and his story elicited by many questions. Upon the stove a frying pan, containing a stewing portion of carrots, simmered as Steve jammed more firewood into the blaze that was heating his dinner.

He hauled forth a shaggy, yet sadly worn pipe for himself and from his seat on the end of a wood box, fanned romance by his talk.

Nineteen fording places in the river back of Steve Mitchell’s cabin mark the old Barlow trail, pathway of the pioneers who first crossed the Cascades around the base of Mount Hood. Mitchell can point out each ford and can tell of the days when he trod the still fresh trail of those empire builders who preceded him.

He will show from his front door the vast, timbered hill where, within his mountain lifetime, has grown a forest. When Mitchell selected his mountainous home there was no sign of woods save the blackened bulk of great trees destroyed by an ancient fire.

He has seen those hills yield heavy timber, where, within the scope of his own memory, there was but a charred reminder of a once deep forest. Over their denuded slopes he has watched by the hour while his dogs ran deer that he might have food, he lolled in their shade times unnumbered as he hauled from their roaring streams great trout to appease the mountaineer’s keen appetite. He has tracked the bear to favorite berry fields and his gun has brought the mountain lion hurtling from his tree.

He has held communion with the lords of nature’s great open spaces, and he has studies their secrets until they are his lexicon-his primer and his Bible.

From it all he has learned both hospitality and hate. He hates civilization; yet he is hospitable to a degree unlimited.

As he spread his Sunday dinner a demand to partake with him declined, he proferred (sic) a piece of his “bachelor pie” that would bring envy to the most dainty housewife. Its flaky crust enough to belittle a salaried chef, the pie he had manufactured, with filling of raisins, was a delicious morsel the he insisted must be followed by a generous slab of light loaf cake he had just drawn from the oven.

“And now,” he jocularly said, “you can stay overnight if it rains real hard.”

“Folks from the towns are taking all the fish from the creeks are we’d have a mess for breakfast too. No, ‘planted’ fish do not restock the streams. Does a hen lay all her eggs in one day, once she gets started? Neither do fish, if they’re left to their natural means, and scientific methods can’t change nature’s way.

“The same civilization that has ‘fished out’ the streams has frightened the few remaining animals back into the mountains, where these confounded thunder buses can’t chug and sputter and roar their dusty way through night and day.

“Between thunder buses and these man-animals down the road one can’t even sleep anymore.

“Civilization is coming too close and I’m about to move back with the deer and the bear and the fish. There are no neighbors there to let their people starve on their doorstep. There is no whopping holler at midnight, but the call of the mountain winds and the cougar’s cry.”

Steve Mitchell’s comfortable little cabin sits beside the road 10 miles west of Government camp, and for many miles around there is hardly a foot of ground that this main of the mountains has not trod and whose charms he has not sought.

He is known to the folk who live in the hills, but to those who come from “civilized” places his is but one of the modest homes that may be found in the wilderness.

His, though, is a home in every sense, for he lives in it in summer and winter, through snow and sunshine. Only upon “occasions” does he venture from his mountain haven and such occasions are all to frequent if they occur more than once in a decade. The sturdy sons who remain in the family drop in now and then to visit with their father or to spend an idle day under his roof. But his wife who saw his early happiness in the hills has been called to “civilization.” She lives at Sandy, where, Steve declares, he has no business. Two splendid daughters hold worthy positions in centers of “civilization”.

Three sons remain of the four reared in the Mitchell family. Lige Coalman, famous Mount Hood guide and forest ranger, whose knowledge of the timbered wilds founded on training at Steve Mitchell’s hands, was reared as a son by this mountaineer and his wife. But Coalman, too, has quit the mountains for the profits of a farm.

When the world war opened the four stalwart Mitchell boys, each loyally attentive to their father and each a convert to the nature-loving, out-of-doors creed of their forebear, were prepared with strong bodies, capable hands and a will for the fray. Mountaineers, each of them, the four enlisted for service. Two were members of the marine corp, one chose navy and the fourth wore an army uniform. The first three were overseas fighting men. Arlie, a strapping young chap wonderfully versed in mountain lore, made 11 round trips over the Atlantic as a member of the nation’s naval forces and did eight months of shore duty overseas, where he visited almost every important city on the continent and in the British Isles.

“I hadn’t been out of the mountains much before,” he says, “and I never want to be again.

The sons who were marines, members of the mow historic fifth regiment, were also initiated to the ultra-modern delights of the world’s capitals, but they gleefully returned to the mountains of their childhood and resumed to their work in the forests.

One of these, a boy respected by every mountaineer who met him, fought through all the hot campaigns in which the American marines mouled war history in France, before he returned to the wooded, romantic land of his choice.

Again in the mountains, held fast by their appeal, this youth, just a year ago, gave his life to the protection of his playground when fire swept through the forest almost within sight of his father’s cabin.

With the same strength and courage that he fought his battle overseas, Steve’s son fought the blaze that would denude his homeland. Nor did he care a whit for the danger that surrounded him when a great fir, rocked upon its fire gnawed base, crashed down upon him.

That was an “occasion,” a day of sorrow for Steve Mitchell. He was drawn to the city-hated Portland-to hear the funeral dirge. And he vows he will never return.

The lonesome trails of the mysterious mountains have felt the footfall of Steve Mitchell. He will not profane the joys the hills have given him by the belated association with the world beyond his forest bound home. “