Intro: This is a story that was transcribed from the retelling by Victor H. White in 1972 of a story from the life of Mount Hood legend, Elijah “Lige” Coalman. In 1972 Victor H. White took transcripts of Lige Coalman’s life as they were recorded by Lige himself. He also had the opportunity to interview Lige to help fill in some blanks. In his own words; “I re-wrote Lige Coalman’s own manuscript, condensed it, re-phrased it, and edited it. I shortened it and omitted repetitious and non-essential material. I did not add, change or exaggerate anything.”

The following story is one of the stories that Victor White left from the book, but felt that it was worthy of retelling in a subsequent publication. The story really does exemplify just how wild and primitive the area from Sandy to Mount Hood really was.

Snow Saga of Lige Coalman

Adventure, danger and unusual happenings along the old Oregon Trail west of The Dalles to Portland were limited neither to the early days before 1860 nor to the fork of the trail that used the Columbia River as a highway.

Westward from The Dalles, the overland route of the wagon-driving immigrants turned first south, then westward south of Mount Hood over Barlow Pass. This route across the Cascades became a toll road with specific charges for each wagon, horseman, cow or sheep which used it and, because of existing government land use laws at the time, there was one man who did something in that locality no one else ever attempted before or since. His name was Dr. Herbert C. Miller, then Dean of the Northwest, Dental College located in East Portland. Doctor Miller established a large farm at Clackamas Meadows directly at the summit of the Cascade Range, some fifteen miles south of the toll road, where snow might fall ten, twelve or fifteen feet deep and there was no access save a mountain trail impassable for several months except on snowshoes.

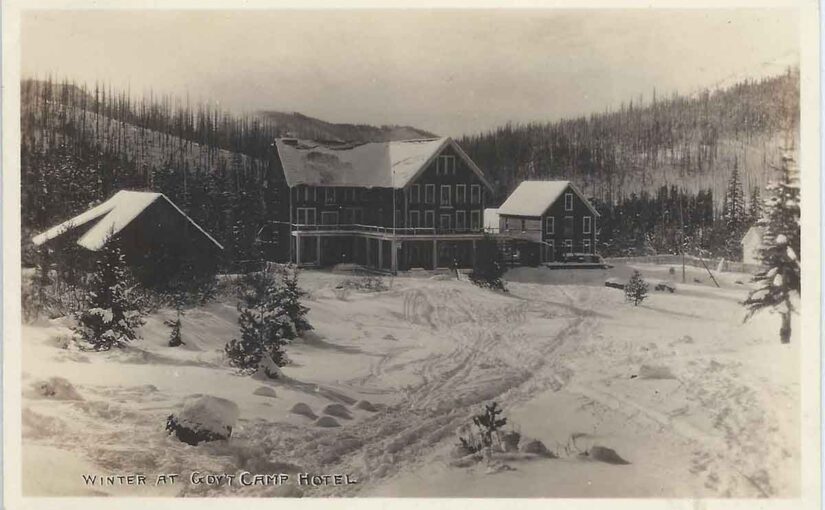

There was then a roadhouse at Government Camp which was also, then as now, the jumping-off place for the start up Mount Hood by the way of the timberline where the ski lodge is today. This accommodation was a mile or so north of where the original Oregon Trail had passed.

On one particular December night in 1914, four men, one woman and two children, the entire winter population of Government Camp, were all sleeping peacefully in the hostelry building when Lige Coalman was awakened by a noise that sounded like something scratching and clawing at the door and moaning or shouting feebly. There was nine feet of snow on the ground and the temperature was near zero.

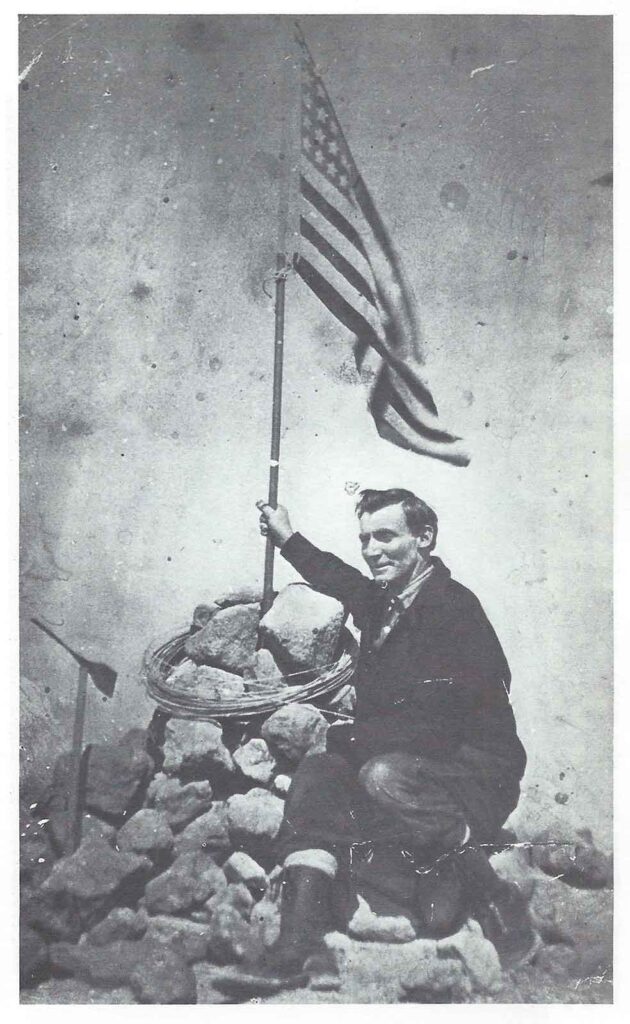

Lige Coalman was thirty-three at the time and perhaps the most capable and experienced mountain man in all Oregon. Those with him in the building, besides his wife and his two children, were a foster brother, Roy Mitchell, and an old timer from Oklahoma named Lundy.

Lige got out of bed and went to the door. His movement and the continued unfamiliar pounding at the door roused the others. Lige opened the door and a man’s body that had balanced against it, fell into the room. This man’s head was completely bound and covered with a wool muffler, although he had evidently arranged a slit for his eyes as he had beaten his way through the storm and finally fallen against the roadhouse door at almost the exact moment of complete exhaustion.

Coalman dragged him forward, closed the door and called to his wife and the others, “Get a fire going; this man’s nearly frozen.”

But warmth already had the fellow able to half sit up and he was desperately trying to explain, “Man, woman and baby… two miles… in snow… will freeze…” He pointed shakily down the mountain in the direction of Rhododendron and Portland.

As soon as the muffler was off the man’s head, Lige Coalman recognized Doctor Miller, Dean of the dental college, who owned the farm at Clackamas Lake. Lige also personally knew the man, woman and one-year-old child who were down the road in danger of freezing. They were the Andrews Family, who had been helping to run the butcher shop in Sandy, Oregon, about 30 miles to the west and below heavy snows.

The three men got Miller into a bed with warm blankets over him. Mrs. Coalman had hot chocolate in brief moments and got busy massaging circulation into Miller’s frosted limbs. Mitchell and Lundy immediately bundled up and started for a frozen location known in the summer as Big Mud Hole on the Laurel Creek Road. Lige spent a few moments helping his wife feed and partially restore Doctor Miller’s circulation, then followed the other men down the mountain.

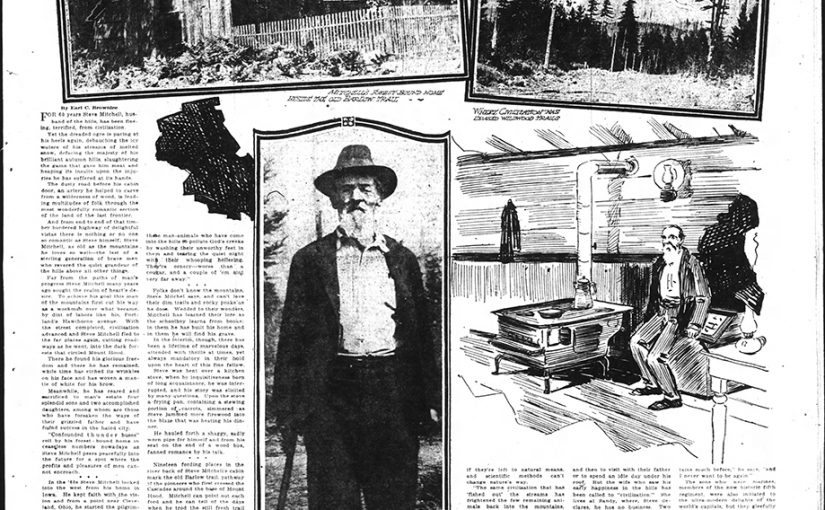

In the early 1900’s tuberculosis was perhaps the most common cause of death in the Northwest among both Indians and whites. It was commonly believed that a high, dry, clean atmosphere was imperative to recovery. Thousands of persons went to Arizona for possible cure but limited finances made this pilgrimage merely a mirage of hope for the wealthy. Nearer to home, high and, if possible, dry hills were often specifically chosen for tuberculosis hospitals and sanitariums. It had come to Doctor Miller’s attention that a particular spot in the Cascade Range at Clackamas Lake seemed to have definite benefits of nature that could serve both as a means of profit and as a boon to mankind as a site for a tuberculosis sanitarium because it was true then as it is now that Clackamas Meadows, situated at the very top of the Cascades, enjoyed a prevailing easterly wind almost as uniformly as the summit of Mount Hood has a never-changing southwesterly wind.

This dry wind swirls air from Eastern Oregon into the high Cascades as happens in no other spot of those mountains. But unlike the southwest wind on Hood, the Clackamas wind does shift in winter to bring in heavy snows from the west.

Doctor Miller’s problem arose from the fact that Clackamas Meadows was within the boundaries of the Mt Hood National Forest which was withdrawn from homestead entry unless proven to be adapted to agriculture. It was this agricultural adaptability that Doctor Miller proceeded to prove in order to claim ownership and build a sanitarium.

He built a log dwelling, barn and other outbuildings, all strongly constructed with roofs that could uphold the possible fifteen feet of winter snow. He plowed several acres of meadow, dug drainage ditches, planted a family orchard and arranged a garden plot. Then he brought in a team of horses, milk cows, pigs and chickens. He truly established what amounted to a Siberian or Canadian home-site. He even went to the extent of panting the meadow to wheat, oats and barley and a variety of timothy which he actually did import from Siberia. A young German named Meyers, with two of his cousins, was employed to run this farm as caretaker during the winter season, when they also picked up several hundred dollars additional income by trapping fur bearing fox, lynx, pine marten and wolverine. Their traps also yielded beaver, otter and mink along the Clackamas River.

Several winters of this, however, had proven enough for the three young Germans. When Meyers was offered a job by the city street car company in Portland, all three farm workers asked Doctor Martin to relieve them and this was why the arrangement had been made to hire the butcher’s helper and his family from Sandy.

That night about midnight, Mitchell and Lundy found the butcher, with his wife and baby, crouched around a fir twig fire they had managed to start on the snow. Partially sheltered by a toboggan loaded with household goods and personal effect, they were nevertheless in critical condition. The baby, having been best protected by the mother, was the only one not suffering frostbite by the time Lige Coalman arrived and they were then able to complete their trip back to Government Camp where they arrived at daybreak. It took four days of warmth, rest and food before they party dared venture on. Then, with Lige Coalman and Mitchell accompanying Miller and his new employees, the party of five adults and the baby undertook the remaining fifteen or sixteen miles of snowshoe and toboggan travel toward Clackamas Meadows.

The strenuous first day of struggle through glaresnow, sometimes ice-encrusted, brought them up about fourteen hundred feet of elevation by noon. They had pulled the toboggan to Frog Lake by two o’clock and Mrs. Andrews and the baby were able to ride the remaining two miles of slight downgrade to an old cabin on Clear Lake by early evening.

Part of the cabin roof had caved in. All but the baby fell to work, using boards as shovels. Thus they cleared the snow from the part of the frozen bare ground, which was still roofed. They felled a dry cedar snag with an axe from the sleigh, got a fire going and then cut fir boughs, which were partially dried to make a mattress, upon which their complete exhaustion enabled them to sleep intermittently for a few hours before dawn.

By 6 a.m. a new wind started snow sifting down on the weary sleepers. By 7:30 they had finished the breakfast they had planned and, after running into a new snow storm at nine, they pressed in and won the relaxing comfort of the snug Miller log house by noon.

Lige Coalman and Mitchell planned to bring the three farmer caretakers back to Government Camp in a fast one day sprint. Before noon, however, one of the Germans, who thought that he had fully recovered from a recent bout with the flu, began suffering a relapse. Before nightfall, he was running a high fever and had to be placed on a toboggan with additional blankets and medicine. By the end of the second day, the sick man was brought to Government Camp suffering high fever and delirium. His life was nip and tuck for almost a week and it was the middle of February before he had recovered sufficiently to go on in to Portland.

Indeed, the hazards and hardships of winter travel in all of the Oregon Trail Country through the Cascade Mountains in 1914 had changed little in sixty or seventy years. Although a doctor was available in Sandy, the means of hisd getting to a sick man at Government Camp through ten feet of snow was hardly a practical undertaking. Even today a sudden snow storm can close the modern highway for indefinite periods while the most modern equipment struggles around the clock to keep things moving between Barlow Pass and Sandy. This can happen most any time from November 1st until the middle of March or even later.

For some twenty miles eastward from Barlow Pass modern man seems to find no use for any kind of highway at all and only a toilsome dirt roadway marks a course for a few intrepid tourists and fisherman who venture for pleasure down Barlow Creek up which the early immigrants struggles to reach the rich agricultural promise of the Willamette Valley and the new world trade center of Portland.