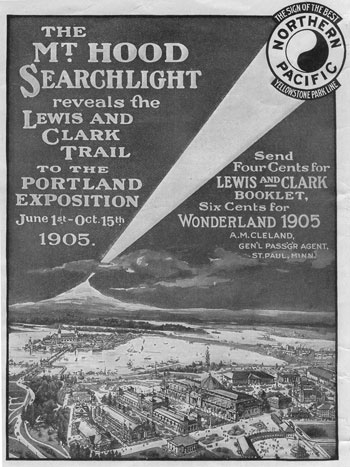

It was 1905, one hundred years after the Corp of Discovery was sent west from the United States into the wilderness to report the makeup of their newly acquired territory, and Portland Oregon was throwing a party to celebrate the occasion. In four months, 1.6 million people toured what was the equivalent to a World’s Fair with exhibits from nineteen states and twenty one different countries. Extravagant, if not substantially built buildings were constructed in the Spanish Renaissance style. It was quite an event with many different publicity stunts to draw attention to cooperators and to the event itself. One of which was an attempt at illuminating the summit of Mount Hood in a way that could be seen from Portland and the Lewis and Clark Expo.

Illuminating Mount Hood was nothing less than an obsession to folks in the late 19th century, as there were many attempts, and a couple successes.

Perry Vickers, Mount Hood’s first full time resident, started a tradition of building a bon fire on Mt. Hood in 1870 that lasted for many years. It was most likely not so much for the enjoyment of the people in Portland, but for the enjoyment of the locals who either participated in the building of the fires, or for those in Government Camp or campers at Summit Meadows, where Perry Vickars had facilities for travelers and campers. After a few bon fires, he was the first to initiate a blaze in an attempt be made visible from Portland. He used magnesium for the flame and was seen from Summit Meadow, but not in Portland. This was in 1873.

Several other unsuccessful attempts were made before two Portland men named George Breck and Charles H. Grove, on their second attempt on July 4th, 1887, were able to illuminate the mountain clearly, and bright enough to be seen in Portland. Their attempts were what gave Illumination Rock its name. Other notable names from the party were acclaimed conservationist William G. Steele, N.W. Durham. Govt. Camp’s first citizen and famous mountain guide Olliver C. Yokum, Dr. J.M. Keene and Dr. Charles F. Adams.

In 1901 plans were being made to illuminate the mountain as a part of the 1905 Lewis & Clark Centennial Exposition. Portland businessman and event co-organizer W.M. Killingsworth wanted an electrical light display featuring a huge statue of Lewis on one side of the mountain, and another of Clark on the opposite side. The logistics of such an event were wholly impractical for obvious reasons. Disregarding the construction and placing of the statues that would indeed need to be massive to be seen from such a distance, taking electricity to the mountain was also impractical, even if generated from the closest stream that could be used to power a generator, it was a fanciful but impossible feat.

On July 4th. 1905 “Plan B” for the illumination of Mount Hood for the exposition was put into place. A party consisting of George Weister, E.H. Moorhouse, Horace Mecklem, Mark Weygant and guide Peter Feldhausen proceeded up Cooper Spur for the summit, arriving at around 6pm. Upon reaching the summit, they held on in the frigid cold until the planned time of 9pm when they ignited the red powder that was to provide the flame. When the flame was ignited a wind blew through, taking some the fire down the mountain, thus subduing the flame making in near impossible to see in Portland, but it was reported at being visible in the Hood River Valley to the north. The party left the mountain top right away.

Many more illuminations were done in the subsequent years, with the most spectacular fire being the one that was done for the Mazama Climbing Club’s 75th anniversary in 1969.

The previous story doesn’t touch on the heliography that was done from the summit of Mount Hood, and will most likely be a subject of another story in the future.