Four Horsepower.

An early automobile pulls in to Government Camp, Oregon under auxiliary power.

Four Horsepower.

An early automobile pulls in to Government Camp, Oregon under auxiliary power.

Timberline Summer circa 1940

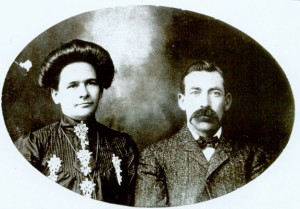

Much has been written about how our local village of Welches got its name, but Welches isn’t the only town that is identified by the family that established it.

Just east of Welches and just past the historic Zigzag Ranger Station you will find Faubion Loop Road. Although a sleepy little residential area now, it once was the settlement of the William J. Faubion family.

William Faubion moved his family to the area in 1907 from the Lents District of Portland. He and his wife Anna settled along the old Barlow Road, which was soon to become the Mount Hood Loop Highway. Just past Zigzag and at the base of Hunchback Mountain they built a home, which they later converted into a roadhouse, similar to our modern day bed and breakfasts. They named it “La Casa Monte”, Spanish for “The Mountain House”.

William Faubion moved his family to the area in 1907 from the Lents District of Portland. He and his wife Anna settled along the old Barlow Road, which was soon to become the Mount Hood Loop Highway. Just past Zigzag and at the base of Hunchback Mountain they built a home, which they later converted into a roadhouse, similar to our modern day bed and breakfasts. They named it “La Casa Monte”, Spanish for “The Mountain House”.

William harvested the huge old cedar on his land, cut shake bolts and hunted to support his family. Several large stumps with springboard notches can still be seen from Highway 26 as you pass by the area. La Casa Monte was completely built from standard dimension hand split cedar boards, with no milled lumber. It was two story with cedar shingle siding, gabled roof and wide eaves. The recessed front porch had arched openings, the center one was reached by a short set of stairs leading to the front door. The interior was rustic with handmade furniture and many animals mounted and displayed, indicating Mr. Faubion’s hunting prowess and the abundance of game in the area. Mrs. Faubion was known for her cooking, particularly her huckleberry pies, making La Casa Monte an ideal destination.

In time, the addition of a store with a post office made Faubion a spot on the map. The post office was established in 1924, and was discontinued in 1932. The store and post office was operated by one of William and Anna’s daughters and son in law, Aneita (Faubion) and Thomas Brown. Many of the early motor car tourists travelling along the old Mount Hood road made La Casa Monte their first stop on their way to adventure on Mount Hood.

In time, the addition of a store with a post office made Faubion a spot on the map. The post office was established in 1924, and was discontinued in 1932. The store and post office was operated by one of William and Anna’s daughters and son in law, Aneita (Faubion) and Thomas Brown. Many of the early motor car tourists travelling along the old Mount Hood road made La Casa Monte their first stop on their way to adventure on Mount Hood.

The Faubion’s had seven children, three boys and four girls. The oldest, a girl born in Gladstone, Oregon in 1890, was named Wilhelmina Jane (Jennie) Faubion. At twenty years old, Jennie married William “Billy” Welch, the son of Barlow Trail pioneers, and homesteaders of the area that would later become the village of Welches, Oregon. Jennie lived in Welches until she died in 1985 at 95 years old. Most of the other Faubion children lived in the area, and were well known and an important part of the history of the Mount Hood area.

Today, the Faubion Area is bypassed by the modern Mount Hood Highway 26, and is known now as Faubion Loop Road. La Casa Monte is gone, the store is still there, but is a private residence now. The residents that live there still know the history of their neighborhood, and identify themselves as living “At Faubion”.

I’ve lived on the old Columbia River Highway in Bridal Veil, and currently live along the course of the Barlow Trail in Brightwood. My love of the Columbia River Gorge and Mount Hood, and my interest in their history has driven my research into the story of both routes and the development of the Mount Hood Loop Highway. Mount Hood is the only glacial peak with a road that completely circles it allowing access to the peak from every direction. It’s a fun day when I can relax and go for a drive the Mount Hood Loop Highway.

Before the immigrants from the East came to settle here the native people had well beaten trails that led from the Columbia River, located to the north, and from the Willamette Valley to the west. The trails led to the hills on the southwest side of the mountain where they would come to hunt, fish, gather berries and harvest medicinal plants.

Before the immigrants from the East came to settle here the native people had well beaten trails that led from the Columbia River, located to the north, and from the Willamette Valley to the west. The trails led to the hills on the southwest side of the mountain where they would come to hunt, fish, gather berries and harvest medicinal plants.

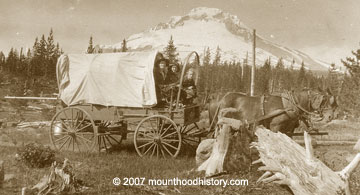

In the early days of the Oregon Trail the “Great River of The West, the Columbia River, was used by the immigrants on their surge west. Many families rafted what was left of their earthly belongings, and in many cases what was left of their families, down the perilous river route through cascading rapids and laborious portages to the Willamette Valley in search of the “Land of Milk and Honey”. Because of this migration, the initial establishment of the overland roads by and large carried traffic from east to west following game and native trails, the primary route being over the southern shoulder of Mount Hood.

Sam Barlow and Joel Palmer arrived in charge of separate wagon trains at The Dalles in September of 1845 and found a shortage of everything, and a long wait for the dicey trip down the river. They both felt that the prospect of staying in The Dalles until a guide could be secured was more than their patience or their budget could endure. Considering the fare charged by the River Guides and the expensive prices for supplies at The Dalles, and the fact that the trip was not just a leisurely float downstream, a land route around Mount Hood sounded like a good idea. Hearing of Sam Barlow’s plan to cross the southern shoulder of Mount Hood, Joel Palmer decided to follow him with his own wagon train, overtaking them soon after.

Moving south along the Deschutes and up the White River they burned and slashed their way to the south shoulder of Mount Hood before succumbing to the arduous labor and the oncoming winter weather which required them to stash their wagons and head in the most expedient way to Fosters Farm and on to Oregon City, with the weaker ones of the party riding their tired stock. December of that same year found Samuel Barlow petitioning the territorial government for a permit to operate a toll road over the path that he and his companions traveled the previous October.

In time several routes were pushed through the Columbia River gorge to the valley, including supply/trade and cattle trails as well as a Military road. By the 1880’s railroads were running through, and of course in 1913 the first paved road was built through in the form of the Scenic Columbia River Highway, of which much has been written.

Meantime on the South side of Mt. Hood Sam Barlow’s road was changing too. Nearly put out of business by the gorge routes, the old Barlow road went through many private hands and states of repair and disrepair before it was handed over to the state to be developed into a highway, much along the same route that we drive today along Highway 26.

By the late 1800’s the immigrants had established their civilization and now many of the next generation wanted to play in the outdoors that their parents fought to survive in fifty years before. Mount Hood is in Portland’s back yard and it beckoned from its position on the horizon visible from most any part of the city, calling them to the mountains. Outdoor sports were very popular then, much like they are today, and many would take the road to the mountain for a guided trip to the summit, or as time went by to the ski slopes in the winter. Summer found them taking wonderful alpine hikes, festooned with breathtaking vistas, fields of wildflowers, creeks and lakes. Fishing and hunting trips were also taken to teaming rivers and the forests abundant with wild game.

By the late 1800’s the immigrants had established their civilization and now many of the next generation wanted to play in the outdoors that their parents fought to survive in fifty years before. Mount Hood is in Portland’s back yard and it beckoned from its position on the horizon visible from most any part of the city, calling them to the mountains. Outdoor sports were very popular then, much like they are today, and many would take the road to the mountain for a guided trip to the summit, or as time went by to the ski slopes in the winter. Summer found them taking wonderful alpine hikes, festooned with breathtaking vistas, fields of wildflowers, creeks and lakes. Fishing and hunting trips were also taken to teaming rivers and the forests abundant with wild game.

Mountain lodges and road houses were established to cater to the tourists, including Welch’s Ranch and Tawny’s Mountain Home as transportation methods and road conditions improved. Horse drawn stages and then auto stages started regular runs from Portland to Mount Hood and back. Many would stop and stay at Welches and others would make the trip to Government Camp where the guides would take them to the top of the mountain.

In 1911 E. Henry Wemme, an automobile enthusiast and Portland businessman, purchased the old road from the Mount Hood & Barlow Road Company with the intentions of improving the route to the mountain and points east for the automobile that was to become the new wave of modern transportation. Two years later he offered the road to the government, who turned down his offer. He died the following year and willed the road to his attorney, who in 1917 presented it to the state who removed the tolls on the road and took over maintenance. By that time there had already been talk of plans for a road that would allow travel completely around Mount Hood.

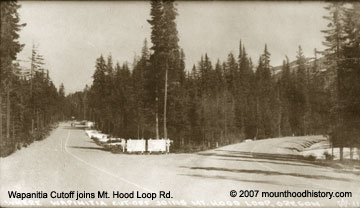

In 1914 Thomas H. Sherrard, supervisor for the Mount Hood National Forest along with William L. Finley, a naturalist, Rufus Holman, the Multnomah County Commissioner, Leslie Butler and Charles Bell from Hood River and Jacob Kanzler of Portland took a horseback trip around the east side of the mountain much along the route of the present highway 35, which created more interest and faith in the feasibility of a route that would follow the upper Hood River Valley around the east side to the Wapanitia cutoff and the south side road.

In 1919 a cooperative agreement was signed between the state and the government to build the road. It was started late in the year of 1919, and was completed in late 1924. The first traffic to follow the new road came in the summer of 1925 after the winter snows cleared. The road was only used seasonally until improvements were made and snow removal started in 1967.

And so the Mount Hood Loop Highway was complete. Fred McNeil wrote that at its dedication the Mount Hood Loop road was called “The necklace about the old volcano with Portland as its pendant”. The Loop hasn’t lost much of its allure since then and is travelled often today by folks out for a “Sunday Drive”. It is easily travelled in a day, including stops for pictures of mountain vistas, waterfalls and lunch. If anything has been lost, it’s the lack of awareness of what is being passed unnoticed by those that are “making tracks” and not “smelling the rhodies” while encapsulated in their climate controlled, surround sound equipped cocoons that travel at speeds not thought of by the pioneers that traveled before them.

Do yourself a favor the next time that you are looking for adventure and take the Mount Hood Loop Highway and please, stop and read an historical marker, or visit a museum. There are many shops and restaurants along the way that are just waiting to be discovered as well. If you’ll leave your cocoon and take a side trip or two and stop and smell the rhodies, maybe you’ll figure out why I love my neighborhood so much. Oh, and wave as you pass Brightwood, it’s right off the highway on a great stretch of the old road.

Do yourself a favor the next time that you are looking for adventure and take the Mount Hood Loop Highway and please, stop and read an historical marker, or visit a museum. There are many shops and restaurants along the way that are just waiting to be discovered as well. If you’ll leave your cocoon and take a side trip or two and stop and smell the rhodies, maybe you’ll figure out why I love my neighborhood so much. Oh, and wave as you pass Brightwood, it’s right off the highway on a great stretch of the old road.

Click here to see vintage pics from the old Mount Hood Loop Highway from Wemme to Hood River.

Click here for Mount Hood Loop Map

It was 1905, one hundred years after the Corp of Discovery was sent west from the United States into the wilderness to report the makeup of their newly acquired territory, and Portland Oregon was throwing a party to celebrate the occasion. In four months, 1.6 million people toured what was the equivalent to a World’s Fair with exhibits from nineteen states and twenty one different countries. Extravagant, if not substantially built buildings were constructed in the Spanish Renaissance style. It was quite an event with many different publicity stunts to draw attention to cooperators and to the event itself. One of which was an attempt at illuminating the summit of Mount Hood in a way that could be seen from Portland and the Lewis and Clark Expo.

Illuminating Mount Hood was nothing less than an obsession to folks in the late 19th century, as there were many attempts, and a couple successes.

Perry Vickers, Mount Hood’s first full time resident, started a tradition of building a bon fire on Mt. Hood in 1870 that lasted for many years. It was most likely not so much for the enjoyment of the people in Portland, but for the enjoyment of the locals who either participated in the building of the fires, or for those in Government Camp or campers at Summit Meadows, where Perry Vickars had facilities for travelers and campers. After a few bon fires, he was the first to initiate a blaze in an attempt be made visible from Portland. He used magnesium for the flame and was seen from Summit Meadow, but not in Portland. This was in 1873.

Several other unsuccessful attempts were made before two Portland men named George Breck and Charles H. Grove, on their second attempt on July 4th, 1887, were able to illuminate the mountain clearly, and bright enough to be seen in Portland. Their attempts were what gave Illumination Rock its name. Other notable names from the party were acclaimed conservationist William G. Steele, N.W. Durham. Govt. Camp’s first citizen and famous mountain guide Olliver C. Yokum, Dr. J.M. Keene and Dr. Charles F. Adams.

In 1901 plans were being made to illuminate the mountain as a part of the 1905 Lewis & Clark Centennial Exposition. Portland businessman and event co-organizer W.M. Killingsworth wanted an electrical light display featuring a huge statue of Lewis on one side of the mountain, and another of Clark on the opposite side. The logistics of such an event were wholly impractical for obvious reasons. Disregarding the construction and placing of the statues that would indeed need to be massive to be seen from such a distance, taking electricity to the mountain was also impractical, even if generated from the closest stream that could be used to power a generator, it was a fanciful but impossible feat.

On July 4th. 1905 “Plan B” for the illumination of Mount Hood for the exposition was put into place. A party consisting of George Weister, E.H. Moorhouse, Horace Mecklem, Mark Weygant and guide Peter Feldhausen proceeded up Cooper Spur for the summit, arriving at around 6pm. Upon reaching the summit, they held on in the frigid cold until the planned time of 9pm when they ignited the red powder that was to provide the flame. When the flame was ignited a wind blew through, taking some the fire down the mountain, thus subduing the flame making in near impossible to see in Portland, but it was reported at being visible in the Hood River Valley to the north. The party left the mountain top right away.

Many more illuminations were done in the subsequent years, with the most spectacular fire being the one that was done for the Mazama Climbing Club’s 75th anniversary in 1969.

The previous story doesn’t touch on the heliography that was done from the summit of Mount Hood, and will most likely be a subject of another story in the future.

Climbing Mt. Hood “Back in the day” – Today I thought that I would post a great story about a typical climb from the 1930’s. I’ve been lucky to have been able to meet many historic figures, or their relatives since I started to pursue my interest in learning the history of Mt. Hood.

This story was forwarded to me through a conversation that I had with Anne Trussell (Harlow) from Sacramento, Ca. Anne is James Harlow’s daughter.

I hope that you enjoy this story.

Gary =0)

James Harlow’s journal entry and photos.

Saturday and Sunday, September 19-20, 1931

James Harlow, Curtis Ijames, Cecil Morris, Everett Darr, Dr. Bowles and Ole Lien

Ole came for awhile at noon, and we made definite plans for the climb up Mt. Hood over this weekend. Then I packed up and went over to Ole’s where we were to meet the fellows from Camas with whom we were going up. They were due at 7:30 but didn’t show up by 9:00 so we made arrangements to go up with Everett Darr and two of his friends. They came by after us by 10:30 and we started by 11:00 PM. Ole and I rode in the rumble seat. Everett’s two friends were Cecil Morris and a fellow named Bowles, a doctor. The car, a Chevrolet Coupe, belonged to Cecil Morris. We were at Government Camp by 12:45 AM Sunday. We didn’t stop at the hotel as Raffertys had gone to bed.

It was very foggy from Laurel Hill to Timberline but was mostly clear at Timberline with a 38-degree temperature. The mountain showed up white with a fresh coat of snow. We started on the climb about 3:00 AM with a fellow from Portland, Curtis Ijames by name, making a party of six.

We ran into snow a half mile above Timberline, and put on crampons half way to Triangle Moraine. The snow was well frozen and we hardly sunk in. There was a very heavy west wind and clouds were rapidly blowing across the mountian. The summit was obscured by the first streak of dawn. On Triangle Moraine there was probably an average of fourteen inches of snow piled into drifts, sometimes four or five feet deep. When the sun came up, we saw some beautiful cloud effects, the most wonderful colors I have ever seen.

When we got to Packs Rocks, we were in the fog and the wind tried its best to blow us off into White River Glacier. Upon reaching the first hot rocks, the wind was so hard we could barely move. At times, we just lay down in the snow and anchored ourselves with our ice axes. It wasn’t bad going up on the Crater Rocks drift until we got on the top of it. Then the wind was so bad it took us ten minutes to go 100 feet. The snow was soft, making the going hard. It was foggy most of the time and ice froze on our clothes. It took us quite a while to go the last 1000 feet because of soft snow.

It cleared up before we got to the top of the Summit Ridge. We looked down on a sea of clouds below 8,000 or 9,000 feet on the south and west and scattered clouds on the north and east. Fleecy strings of fog were blowing across the summit with tremendous velocity. And the gusty wind was so strong as to be dangerous. The rocks were ice-covered and the going was very treacherous. The last 200 feet over to the cabin was terrible.

We finally got to the cabin and went in, as the door was unlocked. It was very cold and the fire we lit in the kerosene stove did little to warm things up. We had arrived at the cabin about 11:30, and stayed about an hour. The shack swayed, creaked, and groaned crazily in that wind. The noise was terrific. Leaving about 12:30, we got down the chute okay but got lost in the fog below Triangle Moraine. The snow had softened and made the going very tiresome in the three and four foot drifts.

We finally got on the right path and got down to Timberline by 4:00 PM. Everett, trying to crank Cecil’s car, which started hard, punctured the radiator. We got it started down the road and he could coast nearly all the way to Rhododendron. Ole and I rode into Portland with Curtis Ijames in his Model T Ford delivery. We stopped at Government Camp and got a bite to eat at Rafferty’s so home by 7:30 PM, thus ending a great trip.

The Battle Axe Inn, in Government Camp was for many years the hub for much of the activity on Mt. Hood’s South side. Many mountain rescues were headquartered from the old inn, as well as community gatherings and parties. Many a cold and tired skier found warmth and rest in front of its grand rock fireplace. Continue reading Battle Axe Inn, Government Camp, Oregon