It’s funny how certain situations can go in a full circle. Even old postcards sent on the other side of the world over 100 years ago can find their way back to their origin. I collect old photos and old photo postcards, especially those with historical significance to the towns and the area that surrounds Mount Hood.

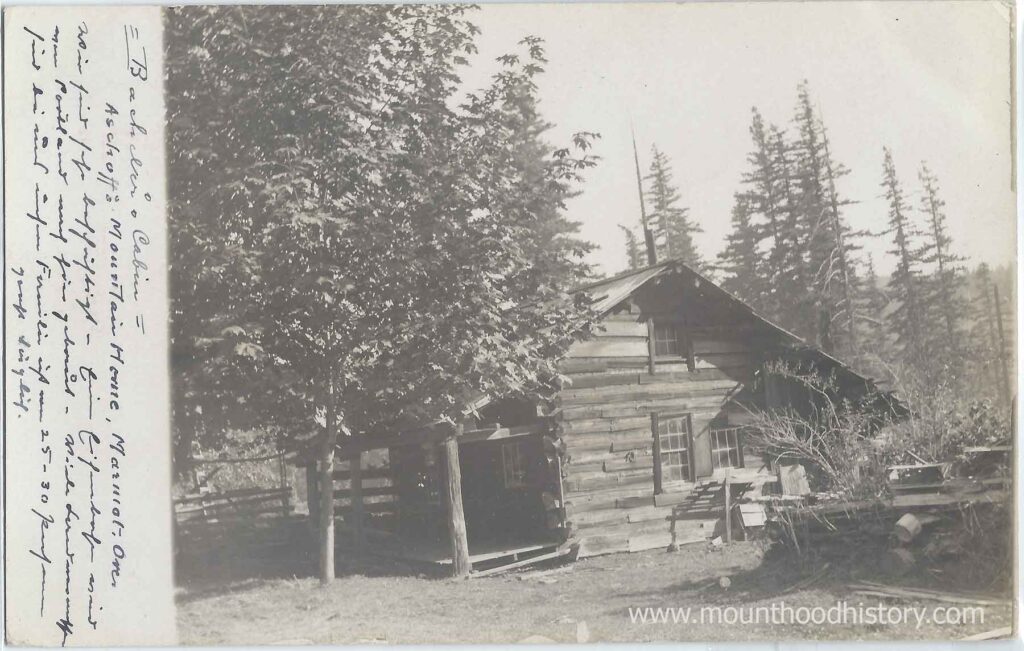

In my searches I found a card on the Internet located in Germany that was from Marmot Oregon, written by Adolf Aschoff and sent to a nephew in Germany. I bought the card and in our conversation I asked if there were any more. The seller told me that he had bought one card in a shop in town but would go back to see if there were more. I ended up buying six cards in all. Every one written in old German language in Adolf Aschoff’s meticulous longhand penmanship. The writing is so small one almost needs a magnifying glass to read it.

Because I do not speak or read German I asked friends if anyone could help. My friend Bill White said that his German friend, who lives in Germany, might be able to help. I scanned the messages and then emailed them to Bill who forwarded them to his friend.

Some time passed and Bill forwarded six MS Word Documents to me with the messages typed in German as well as their translation in English. I was so excited and grateful.

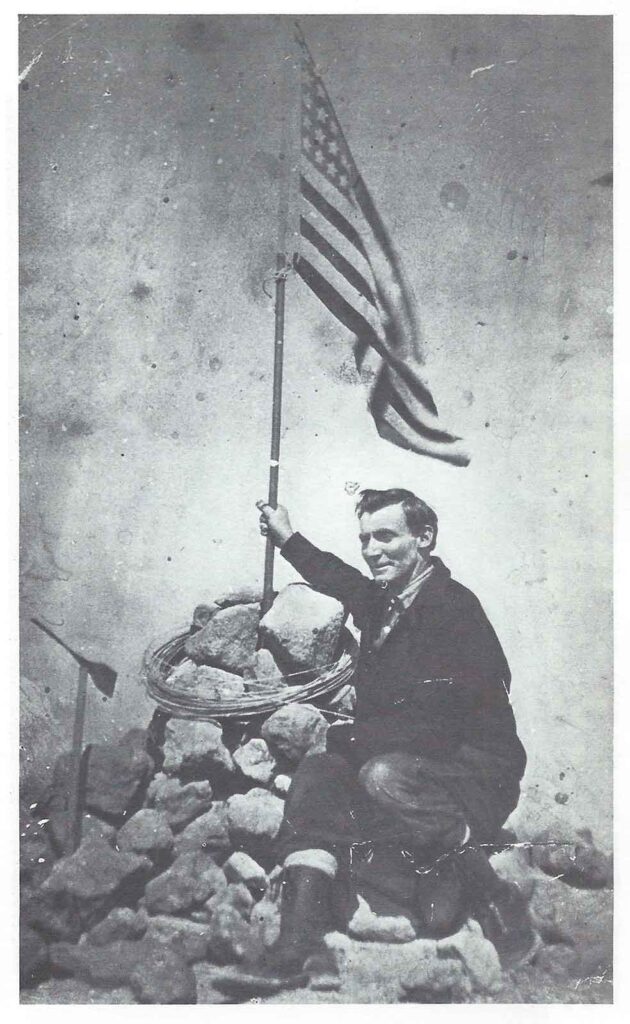

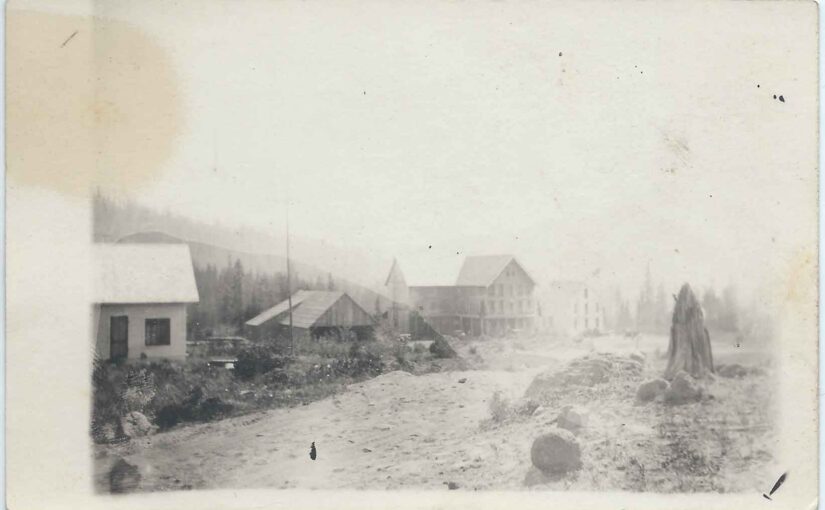

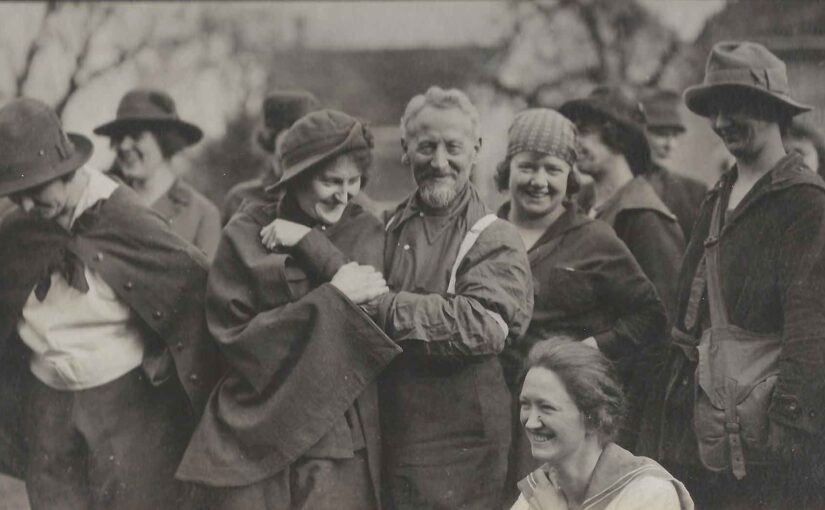

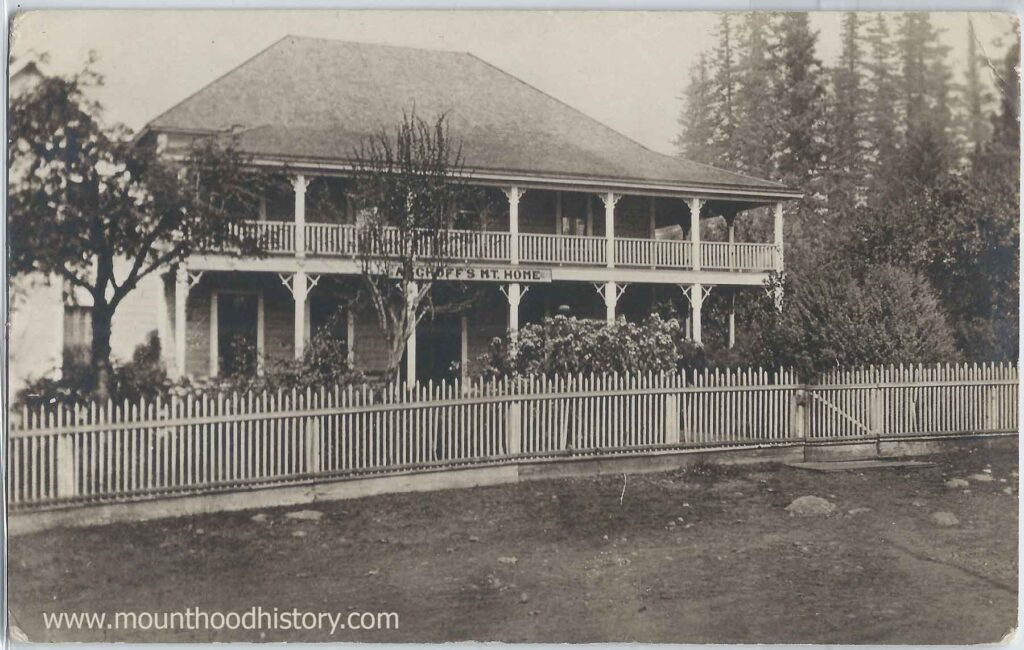

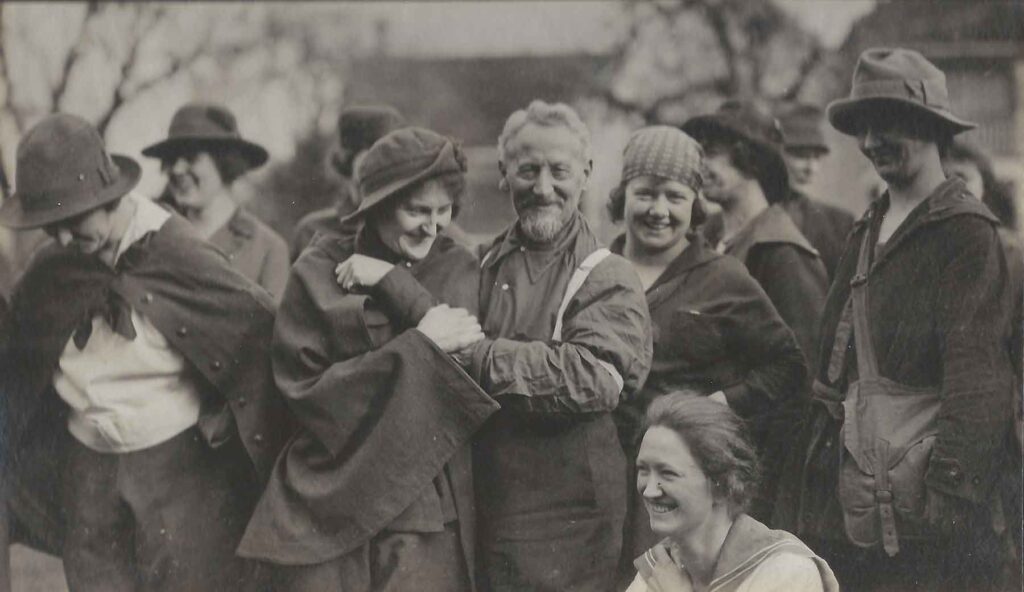

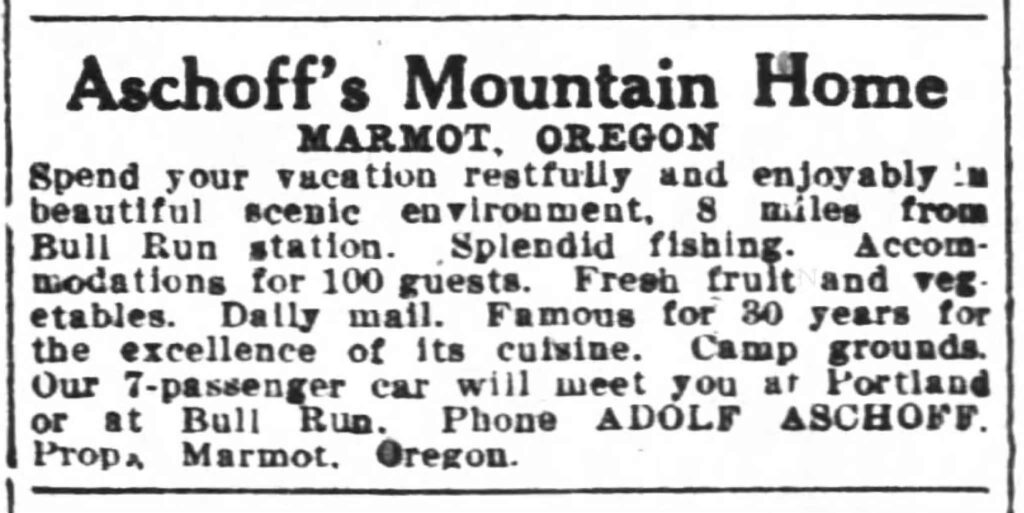

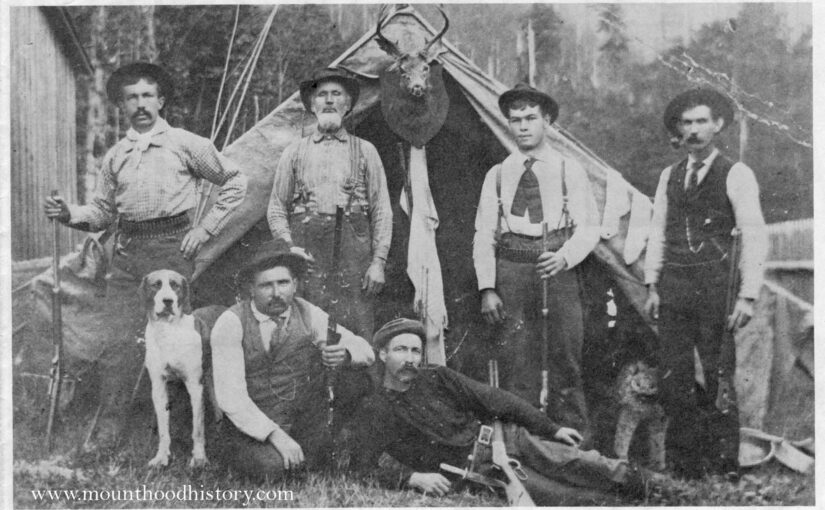

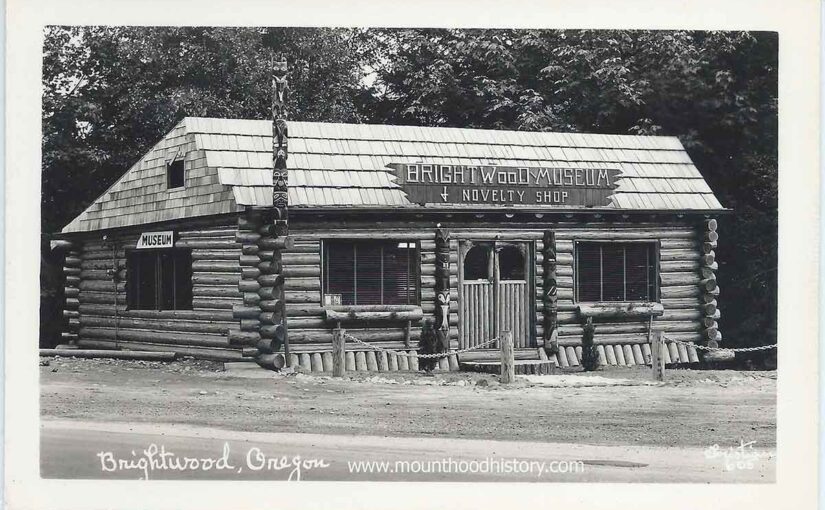

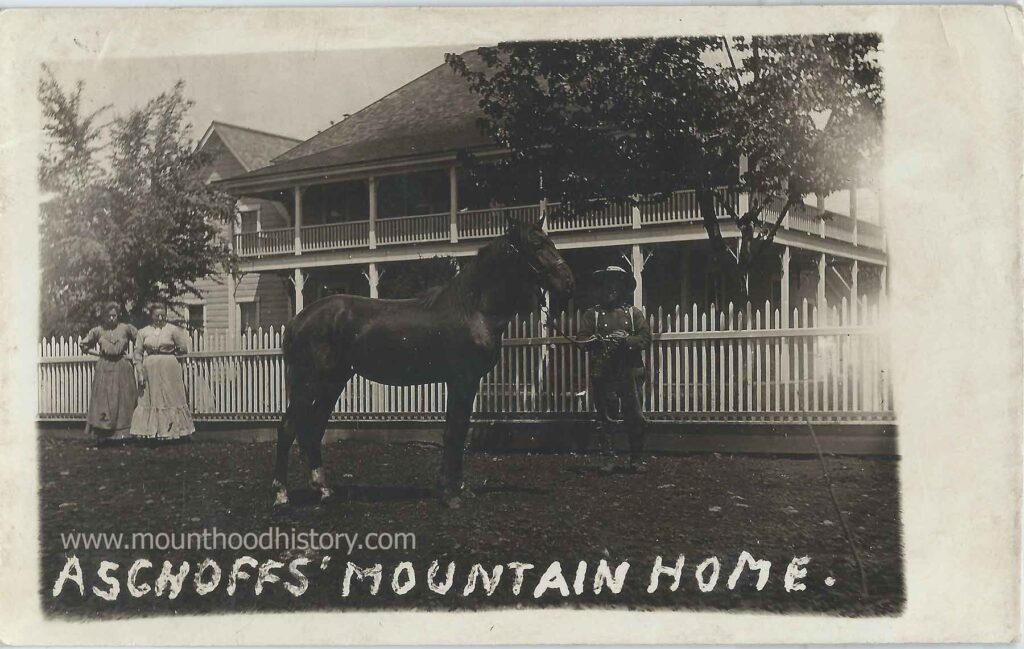

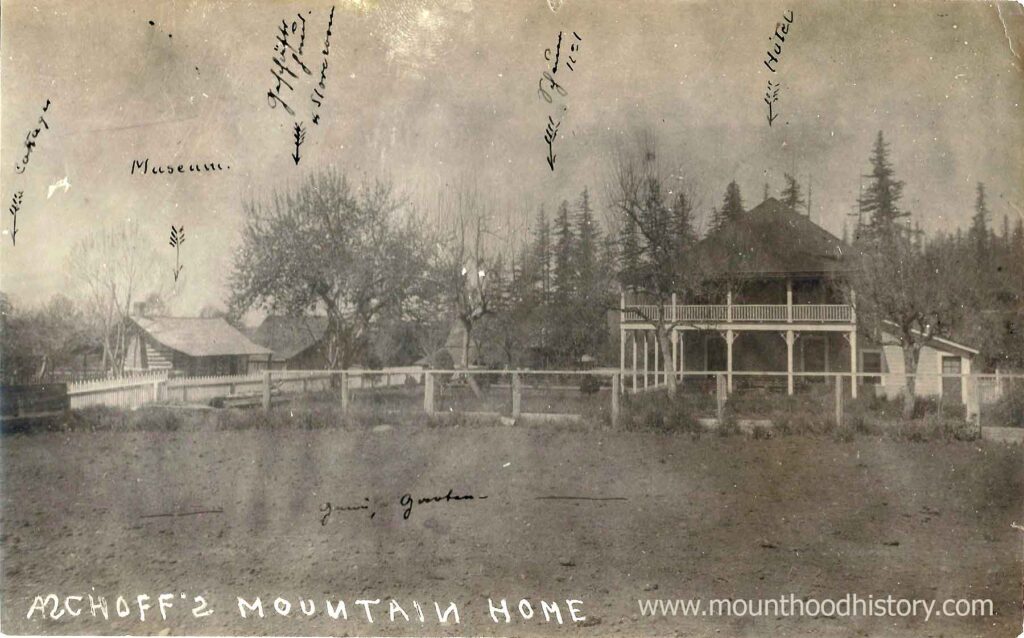

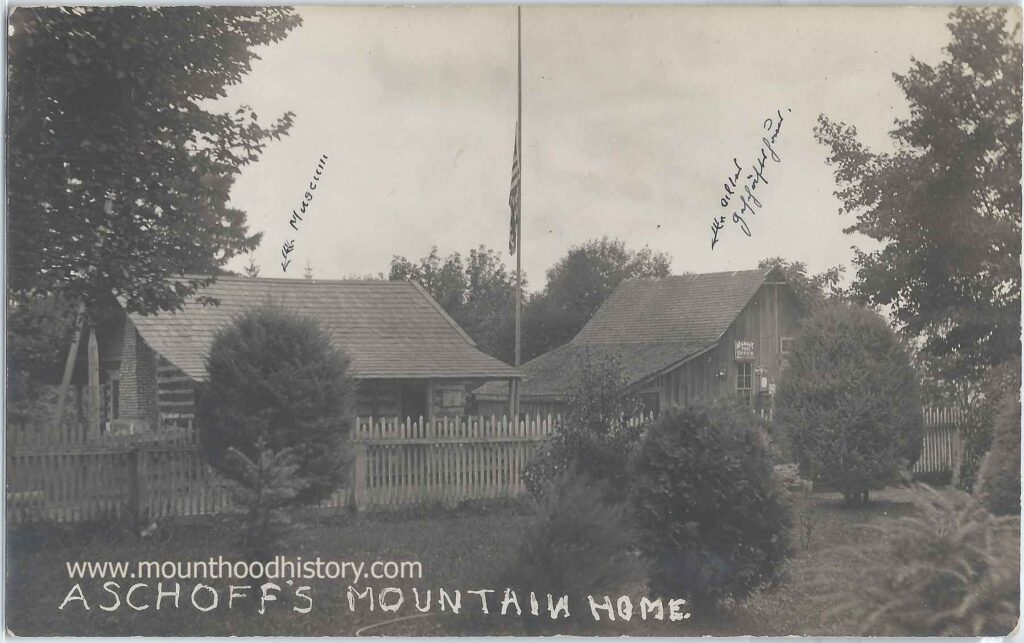

Adolf was from Celle Germany. He settled in Marmot in 1883 and built Mount Hood’s first resort, Aschoff’s Mountain Home. He was known for his cheerful and enthusiastic demeanor. He was the prefect host who catered to and entertained his guests and everyone who talked about him described him as cheerful and energetic, but these correspondence paint a more intimate picture of Adolf. Life for him was not easy and had a lot of worry, stress and heartbreak. For more information about Adolf and the town of Marmot you can read about it at this link. CLICK HERE

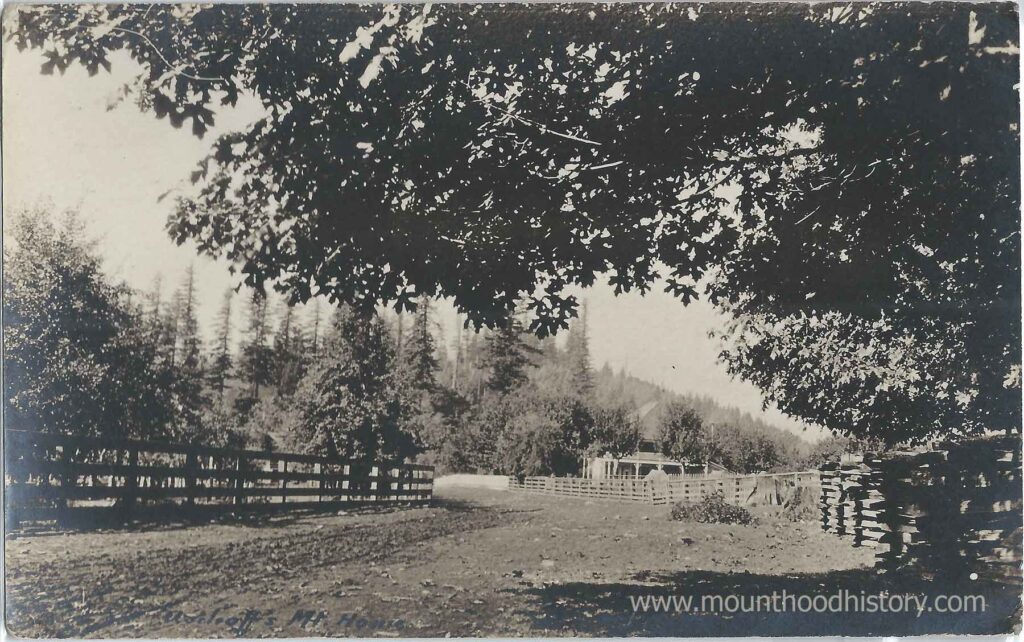

Below are the photos and their messages.

Adolf Aschoff’s Letters To Home

Marmot, Oregon, July 16, 1908

My dear Otto!

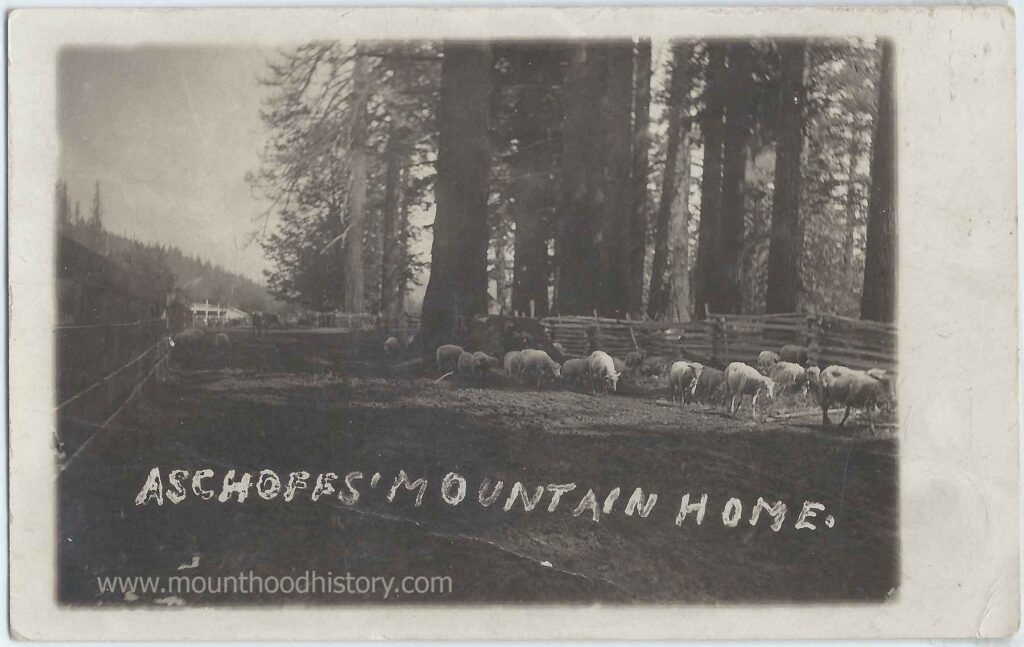

It always goes on in business, from early in the morning to late in the evening. A lot of annoyance and little joy is my experience. Again I just lost a beautiful horse, my wife thought a lot about the (poor) animal. She called it hers. We have a lot of rain and it is quite cold and then we have very deep paths again – everything seems to go wrong, even in nature.

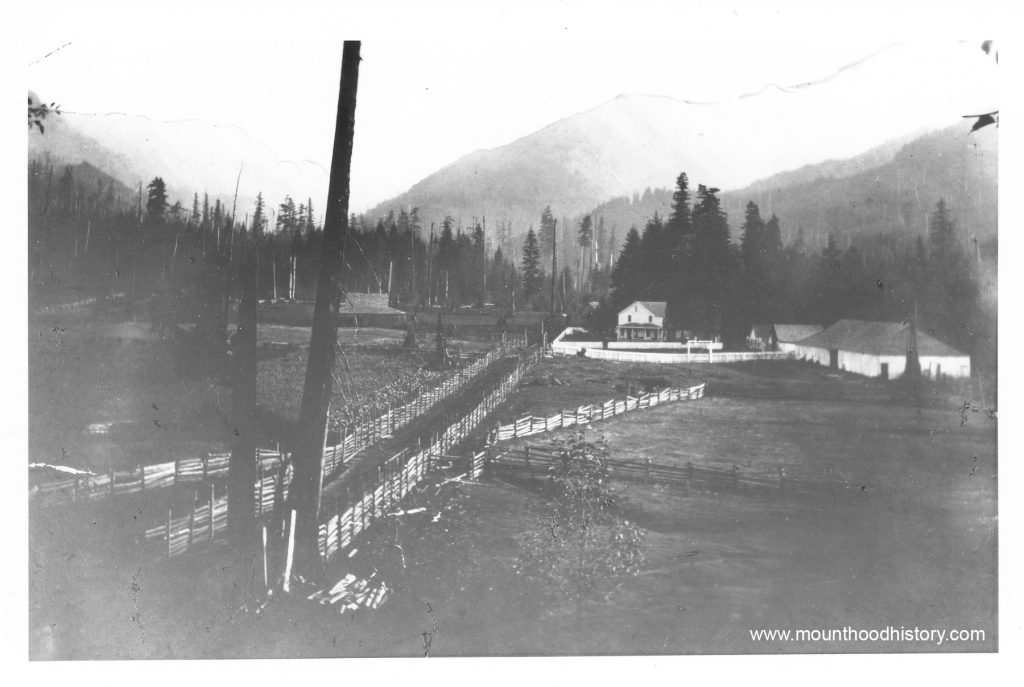

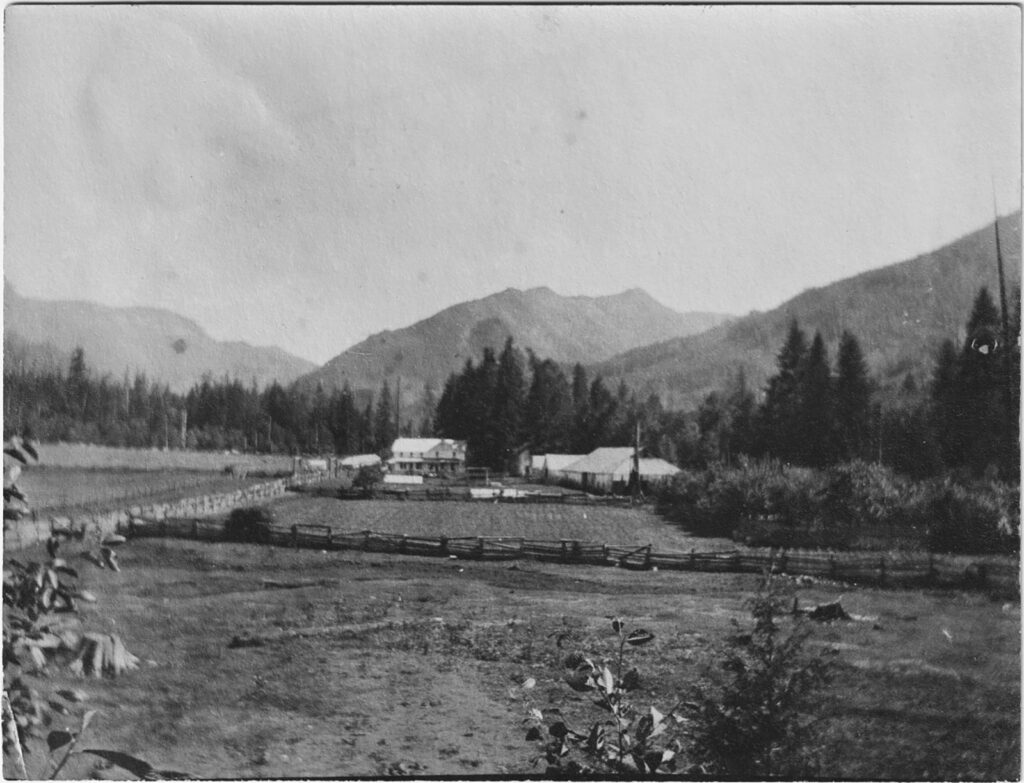

On the other side (of the postcard) you can see our house. No. 1 is my wife, No. 2 is a maid. I keep my two year old German stallion.

Best regards. Your old (friend)

Adolf Aschoff

Marmot, Ore. March 22, 1910 6 am

Dear Otto!

We are desperately awaiting a sign of life of you from the old homeland with every incoming mail – and from day to day – week to week etc. I am trying to find the time and opportunity to write to you. I have not been well for quite some time now – I suffer headaches – melancholy etc. I wish I could sell us – had a great offer but my wife wasn´t please. If I don´t try to visit Germany soon – I will probably never see it again. Both of our sons, Ernst and Henry, are now fathers of two strong boys. – We had an awful time with our three daughters in the last year – all three of them had major operations in the hospital, and now our Emma is back at the hospital and is being operated again.

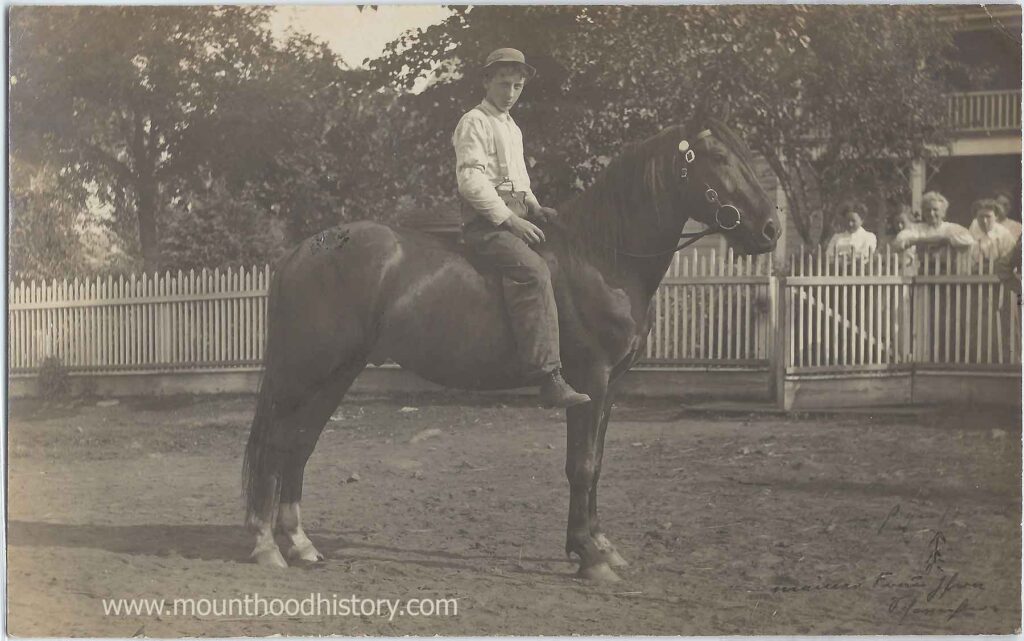

On the other side (front side) you see Gustav, our youngest son on a foal, as he was riding it for the first time, he is 15 years old.

Please, write to me very soon.

Have a happy Easter wishes you your uncle

Adolf Aschoff

Marmot, Ore. July 19, 1910

Dear Otto,

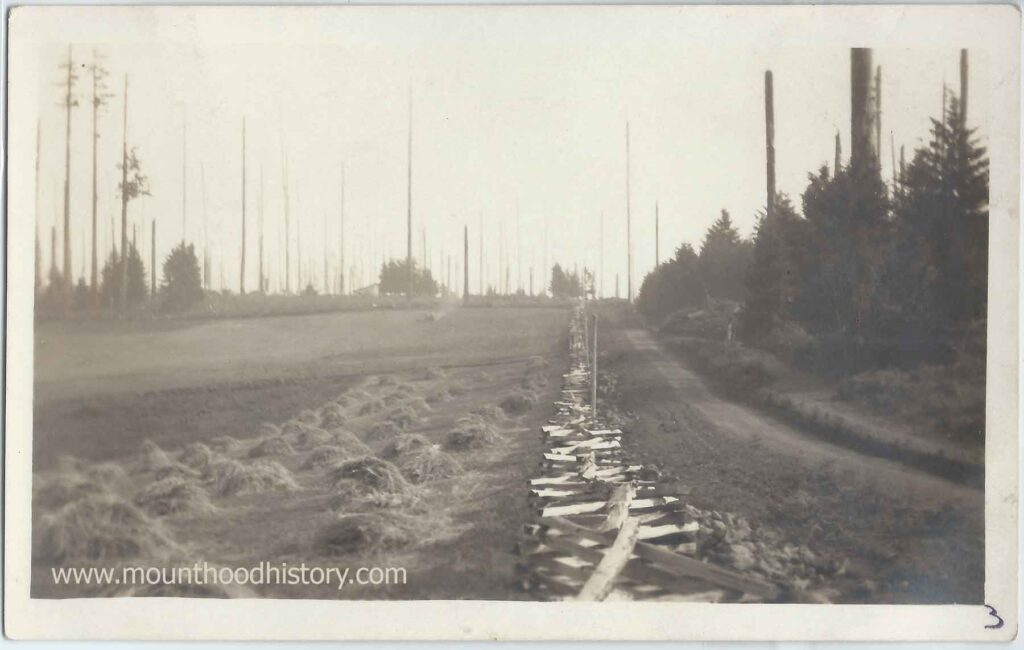

Your endearing letter has been received. Your letter has doubled the desire to see you and the beloved old homeland – I know I would be welcome at your home and if you knew me better, you would know that a westerner does not cause any inconvenience – We have loads of trouble, loads of work – with the hay harvest and everything adds together – The salary for the workers is very high – chef (lady) $70.00 per M, house maid $20-25.00, day laborers $2.50 – $4-5 per day. I don´t know how this is going to end. All workers only want to work 8 hours – but we are usually working 18 hours a day – will write as soon as I have a few minutes to myself

Best wishes from all of us,

Your uncle Adolf Aschoff

Marmot, Ore. February 25, 1911

My dearest Otto,

I hope you have received the newspaper “The Oregonian”, I am sending you the same one, so you can get an idea of the growth of the American cities. As we arrived in Oregon, Portland was about the size of Celle – now Portland has more than 230,000 citizens. We are well, except for Otto, who has been in the hospital for months. Best wishes to you and your dear family.

Your uncle Adolf Aschoff.

PS: I will try to write you a letter soon.

Marmot, Ore. 6/13/1912

My dear Otto,

I haven´t heard anything from you for quite some time now, I try to receive a sign of life, “an answer” to this postcard. I am sending you a newspaper with this letter and I send more if you are interested.

Various accidents have again happened to our family. Our daughter Marie is very sick – our son Ernst has fallen of a …?…. post and our son Otto has chopped himself in the leg. Due to the incautiousness of a stranger I have been thrown of my carriage and I suffer pain in my right arm and shoulder. More work than ever, I wish we could sell us, it is getting to much for my wife and me – from 5 am to 11 pm day to day we slave away (like ox) without a break. Dear Otto, I hope you and your loved ones are well and at good health.

The most sincere wishes from all of us to you and your dear family.

Your uncle Adolf Aschoff

Boys on “Juicy” in the orchard”

Marmot, Ore. January 30, 1913 – To: Mrs. Adele Aschoff

My dear friends,

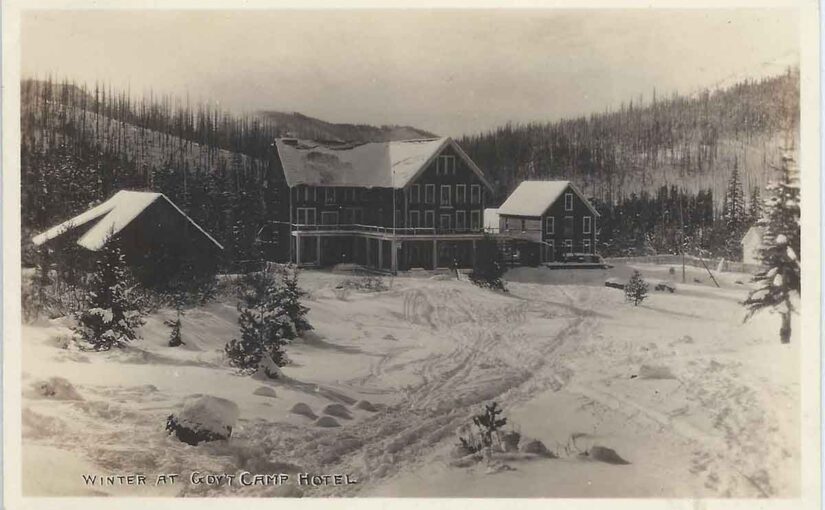

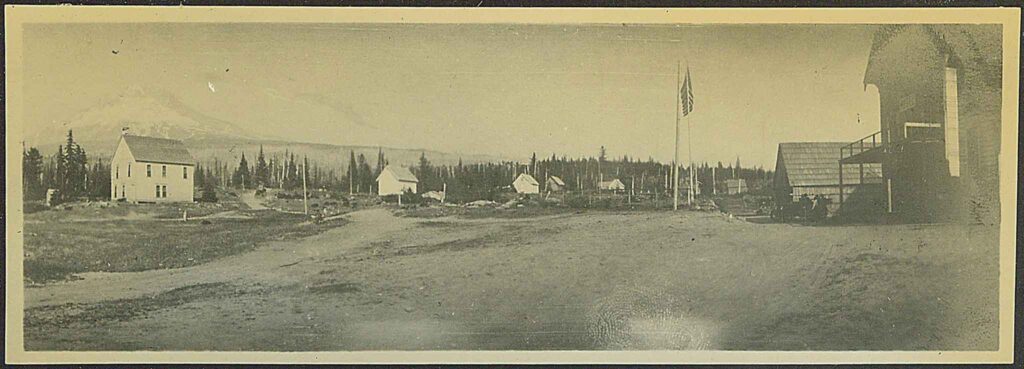

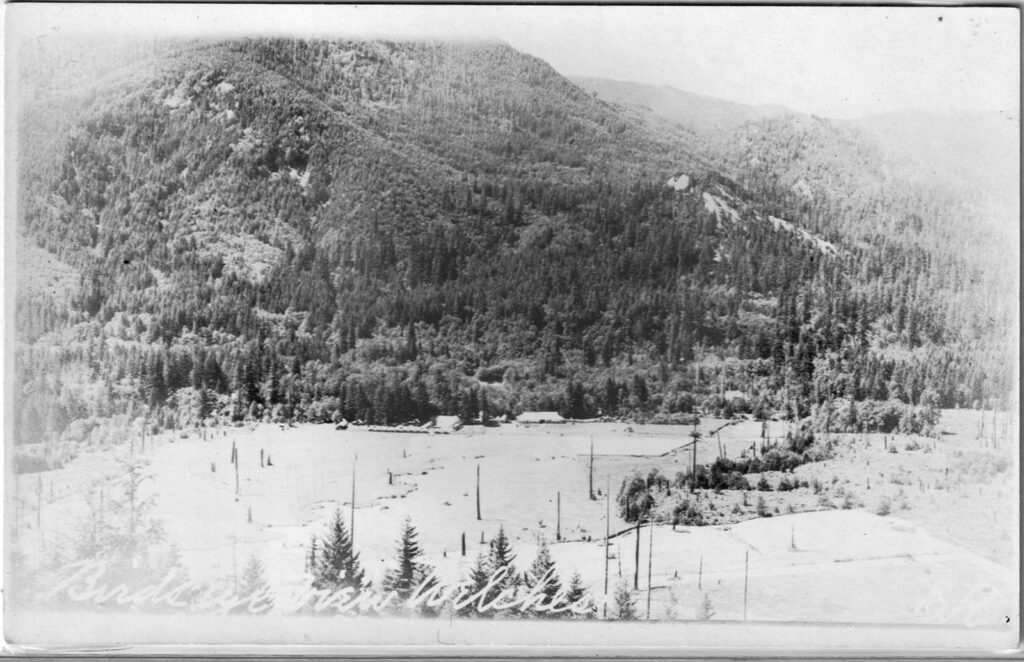

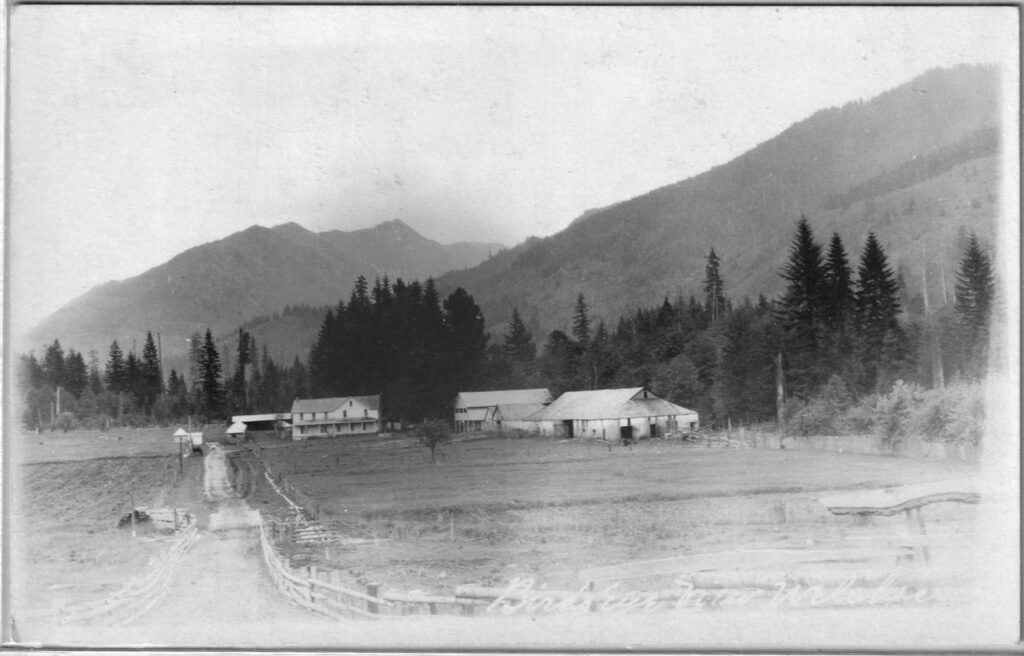

Marmot shows a different picture these days than on the other side of this card. The snow has started to melt, but it will take a long time until the last traces will be gone.

Our dear daughter Marie is still very sick, it is better on some days and then she suffers bad seizures.

Best wishes,

Your Adolf Aschoff

Marmot, Ore. Nov. 19. 1916

My dear Adele, (Mrs. Adele Aschoff)

Thank you very much for your wishes – I am very happy that our dear Otto is still healthy and I hope that he soon will be back with his loved ones well and brisk. Please send him my best regards. I haven´t received anything from Eugen in the last months – newspapers etc. No news have arrived since February from you as well as Eugen. My son Karl has broken his arm when he started (? “up-winded”) an automobile – my wife is very sick again. Please write back to me even if it´s only a few lines.

With the best regards

Your uncle Adolf Aschoff

#adolph #adolf Aschoff #marmot Oregon